Addressing the risk: Policy framework

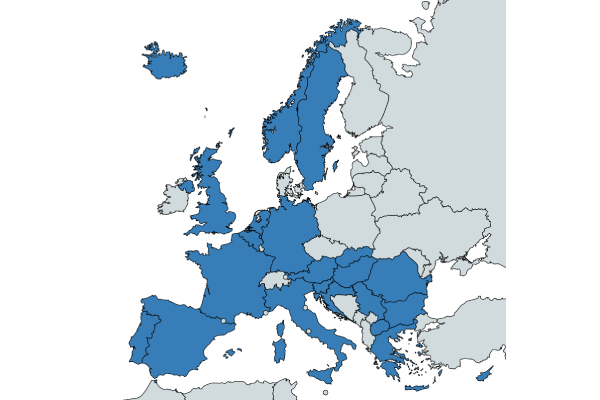

The European Commission supports the development of European building standards – Eurocodes – of which Eurocode 8 (EN 1998) guides the design of buildings, bridges, silos, tanks, pipelines, foundations, towers, masts and chimneys in seismic areas. These standards allow for new buildings to be better designed and, to a certain extent, existing structures to be renovated and adapted. This ensures that if a geophysical event, such as an earthquake, occurs, lives are protected, damage is limited, and civil protection structures remain operational. Special structures, such as nuclear power plants, offshore structures and large dams, are outside the scope of EN 1998.

According to a JRC report on the ‘State of harmonised use of the Eurocodes’, however, seismic zone maps show discontinuities in the seismic levels at countries’ borders due to different national practices, making it difficult to harmonise the use of Eurocodes in neighbouring regions of different Member States.